Lectures

Keynote Lectures

LECTURE

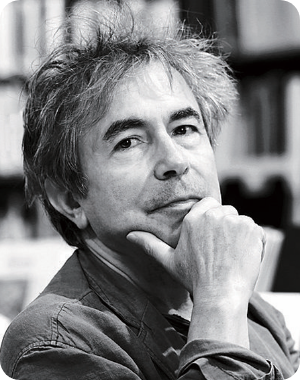

FRANÇOIS JULLIEN

A former professor at the Université Paris Diderot, François Jullien is one of the most influential figures in contemporary French philosophy. His work lies at the crux of sinology and general philosophy. Grounded in ancient Chinese Studies, Neo Confucianism, and the literary and aesthetic concepts of classical China, it questions the history and categories of European reason by creating a perspective between cultures. By dint of this detour through China, the work of François Jullien has thus opened up productive yet exacting pathways to think interculturality.

A Topic of Our Generation, the Reasons for Cultural Diversity

-

DATE

24th June (Sat), 17:30-18:30

-

VENUE

GP(Global Plaza) 2F Hyo-seok Halll

VIDEO

Abstract I - The diversity of cultures

The diversity of cultures is the world’s present, both its relevance and its richness. Ours is a fragile and fertile moment: the world now intersects sufficiently for its diversity to be encountered, and diversity is not yet buried under the steamroller of standardization. - Or perhaps it’s already too late: hasn’t diversity already been lost? But could we not rebuild this Diversity, forever lost to the Traveler, in our minds? For it is true that these cultural resources are under threat, just as so many of nature’s resources are today. Already, the multiplicity of languages is being reduced before our very eyes, at an accelerating pace, to the convenience of Globish and its widespread Communication under the pressure of the global market. At the same time, new nationalisms are emerging that claim to confine cultures to stubborn allegiances, claiming their “identity” with complacent clichés and aiming for imperialism. In fact, isn't one the correlate of the other, as if one could compensate for the other? Will we die under the boredom of one (the loss of Diversity) or the stupidity of the other (the claim to identity)? Or will we not die from both, one dragging the other in its wake?

One thing, consequently, is certain: we need to find another way out of this impasse in which the human being tends to wither away instead of unfolding; one that unravels this knot of constraints, thwarts its fatality, and henceforth posits inter-culturality as the dimension of the world – the dimension that “makes the world”. But what will “inter-culturality” mean if we don’t abandon the term to its mere poster effect? If we want to make it the ethical and political term of a common future for humanity? Because, as we well know, the cultural only ever happen singularly: a language, an era, an environment, an adventure of the mind, the sudden audacity of a thought... What, then, must this between, in “between cultures” imply – as well as in the intra culturality of one culture, if indeed it is “one” – in order for a reflexive, operative, inter-active vis-à-vis to happen, enabling us to explore the gaps between these singularities, so that those singularities, establishing themselves opposite each other, can effectively begin to “exchange”? Haven’t we spoken too comfortably of the “dialogue” of cultures, contradicting the clash which threatens today, without probing the condition of its possibility? Because for a start, in what language will this dialogue take place?

II - What’s in it for philosophy?

This is why the question of inter-culturality is of immediate interest to philosophy, which is positioned within the universal, and rightly so, it believes. It “interests” philosophy at its heart or center, and not in a peripheral, marginal or “comparative” way – such a comparison remains external, decorative, and doesn’t work. Philosophy is henceforth called upon to leave Europe, by a necessity internal to its vocation, to rise outside its own language and history, to encounter other languages and other thoughts whose resources it cannot imagine from within its own language and thought. Who could dispute that this is a matter of urgency, before such a possibility is swallowed up by so-called “global” thinking: not universal, as we would readily believe, but uniform and standardized? These resources from elsewhere reveal other possible paths of thought, or, let’s say, other configurations of the thinkable. As a result, they question philosophy about what it doesn’t think of questioning. No longer only about what it thinks, but about what it doesn’t even know that it isn’t thinking about, what it hasn’t thought of thinking about: what has (European) philosophy missed out on?

For philosophy, this is much more than a critique or a new moment in its history. Because it is precisely a question of emerging at last from its history, from both its connivance and its atavism. By giving it something to think about, from the outside, in return, and firstly on the singularity of its advent, these resources from elsewhere encourage philosophy to probe its implicit choices, its buried biases, naively emerging as “evidence” (the “natural light” of the Classical Age), in other words its unthought: what its thinking is unknowingly based on – thereby putting its Reason back to work. Throughout the twentieth century, the greatest philosophers, from Husserl to Merleau-Ponty and Derrida, let glimpse that philosophy had known a “Western” destiny – but what does “Western” mean? And first of all, in these two joint dimensions of logos and Being, in other words, of “logo-centrism”? Such concern had already beset Nietzsche, the first philologist of philosophy – Hegel being content, as we know, in his History of Philosophy, to let philosophy be born in the East (where the sun “rises”...), but only to have it effectively come into being in the West: at sunset, when Minerva’s owl rises, and under the Greek invention of the concept becoming the main instrument of thought. Now, a new time is dawning, in which languages and thoughts from elsewhere are to be actively brought into the philosophizable.

However, when we say that (European) philosophy must “meet with” other thoughts, the formula is still too easy because it presupposes possibilities that have already been granted. For how can thoughts expressed in different languages be effectively brought into contact with each other, especially if these languages are not of the same language family, as is the case in the Indo-European, and, moreover, are part of cultural contexts that have ignored each other for so long? How can they effectively “open up” to each other, so that one thought can hear the other’s reasons from this Other’s point of view, without immediately dragging them back into the clutches of its prejudice, or rather, further ahead of time, of its pre-thought – pre-notioned, pre-supposed, pre questioned – and this on both sides? “Reasons”: doesn’t this term also come too soon, is it not itself too narrow – doesn’t it already need to be reopened and reworked

More generally, how can two experiences of both life and thought be understood in relation to each other, and maybe even through the mediation of each other, when at the same time they have been exclusive of each other, and when one side initially encounters so many difficulties in starting to stammer in the other’s language? Unless we start by positing some kind of universal, which can only be of ideological rather than logical content, or postulating a given human nature, we can only begin to risk it at the cost of infinite trial and error, which each time, gives us something to think about, vertiginously questioning thought in what it doesn’t know how to think about; and thus calls for so many approximations and corrections, comments and explanations, gradually weaving an in-between [entre] – of inter -culturality – where the encounter can take place. So, through persevering work of elaborating of the between, and firstly, of translation, at least if we understand that to translate is not to straightaway put one under the other, to transpose one into the language of the other, but to overflow the languages through each other and begin to set up the conditions of possibility of this between . Only then will it be possible, patiently and through mutual intelligence, to gradually create a shared field of both experience and thought. Otherwise, we’ll think we have “dialogued”, but we won’t even have begun to approach . We will have remained in the semblance of a pseudo-dialogue. But this is not ancient history, or pitfalls avoided at a moment’s notice, for the risk is undoubtedly even greater today, in a regime of globalized Communication.

III- The universal, the uniform, the common

To enter this debate, we need to clarify the terms, otherwise we’ll get bogged down. This applies first and foremost to these three rival terms: the universal, the uniform and the common. Not only do we run the risk of confusing them, but we must also cleanse each of them of the ambiguity that taints it. At the vertex of this triangle, the universal itself has in fact two meanings that must be distinguished – otherwise we won’t understand where its sharpness comes from, nor what is at stake for society. The first is what we might call a weak sense, of observation, limited to experience: we note, as far as we have been able to observe so far, that this is always the case. This sense is general. It is unproblematic and unobjectionable. But the universal also has a strong sense, that of strict or rigorous universality – which is what we in Europe have made a requirement of our thinking: we claim, from the outset, before any confirmation by experience, and even without it, that such and such a thing must be so. Not only has it been like this up to now, but it cannot be otherwise. This “universal” is no longer simply one of generality, but one of necessity: a universality that is not de facto, but (a priori) de jure; not comparative, but absolute; not so much extensive as imperative. It was based on this universality, in its strong and rigorous sense, that the Greeks founded the possibility of science; it is on this basis that classical Europe, transporting it from mathematics to physics (Newton), conceived of “universal laws of nature” with the success we know.

But with this, the question arises, dividing modernity: this rigorous universality to which science owes its power; as the universal applies its logical necessity to natural phenomena, or mathematics to physics, is it just as relevant to conduct? Is it likewise relevant in the ethical domain? Is our conduct subject to the absolute necessity of moral imperatives, “categorical” (in the Kantian sense), like the a priori necessity that has made physics such an undisputed success? Or should we not claim, in the separate domain of morality, in the (secret) retreat of inner experience, the right to what is to be thought of as the opposite of the universal: the individual or the singular (as Nietzsche or Kierkegaard have done)? The question arises even more because, in this sphere of subjects and, more generally, of society, we can see that the term “universal” hardly ever escapes its ambiguity. When we speak of “universal history” (or “universal exhibition”), the universal seems to be one of totalization and generality, but not of necessity. But is the same true when we speak of the universality of human rights, and do we not then credit them with a necessity in principle? But where is the legitimacy? Is it not abusively imposed?

The question arises even more today, given that we have since had this major experience. In fact, it’s one of the decisive experiences of our time: we are discovering today, as we encounter other cultures, that this demand for universality, which has driven European science and which classical morality has claimed as its own, is nothing less than universal. But that it’s rather singular; that is, the opposite, being – at least when brought to this point of necessity – proper to the cultural history of Europe alone. And firstly, how does one translate the “universal” when one leaves Europe? This is also why this demand for the universal, which we in Europe had comfortably placed in the credo of our assurances, in the principle of our self-evidence, should finally become salient again, in our eyes coming out of its banality, appearing inventive, audacious, and even adventurous. Some might even discover, from outside Europe, a fascinating strangeness to it.

The notion of uniform is equally ambiguous. One might actually think that it is the fulfillment and realization of the universal. But, in fact, it is its flip side; or rather, I’d say, it is its perversion. For the uniform is not a matter of reason like the universal, but of production: it is nothing but the standard and the stereotype. It stems not from necessity but from convenience: isn’t uniformity cheaper to produce? Whereas the universal is “turned towards the One”, the One being its ideal term, the uniform is merely the repetition of one, “formed” in an identical way, and is no longer inventive. But this confusion is all the more dangerous today, when globalization means that we see the same things reproduced and disseminated throughout the world. As these are the only things we see, because they saturate the landscape, we are tempted to credit them with the legitimacy of the universal, i. e. with a necessity in principle, when in fact, it is nothing more than an extension of the market and its justification is purely economic. The fact that, thanks to technical and media means, the uniformity of lifestyles, objects, and goods, as well as discourses and opinions, now tends to cover the planet from one end to the other, does not mean that they are universal. Even if they were to be found absolutely everywhere, a ‘what ought to be’[devoir-être] is lacking.

If the universal is a matter of logic, and the uniform belongs to the economic sphere, the common has a political dimension: the common is that which is shared. It was from this concept that the Greeks conceived the City. In contrast to the uniform, the common is not the similar; and this distinction is all the more important today, when, under the standardization imposed by globalization, we are tempted to think of the common in terms of reduction to the similar, in other words, to assimilation. But this common of the similar, if it is a common at all, is poor. That’s why, on the contrary, we need to promote the common that is not the similar: only this is intensive; only this is productive. This is what I’m here to claim. Because only the common that is not the similar is effective. Or, as a French painter of modernity, Braque, put it: “the common is true, the similar is false”. And he illustrated this with two painters: “Trouillebert looks like Corot, but they have nothing in common.” This is the crucial point today, whatever the scale of the common we’re considering – the City, the nation, or humanity: only if we promote a common that is not a reduction to the uniform, will the common of this community be active, effectively giving people something to share.

The common is not decreed, as the universal is, but is partly given: such is the common of my family or my “nation”, which comes to me by birth. Partly, it is something that is decided, and properly speaking, chosen: such is the commonality of a political movement, an association, or a party, of any collective commitment. As such, this commonality of sharing is distributed progressively: I have something in common with those closest to me, with those who belong to the same country, with those who speak the same language, but also with all humans, indeed with the entire animal kingdom, and even more broadly, with all living things – with this wider commonality ecology is now concerned with. Sharing the common is, indeed, in principle, extensive. But this “common”, as such, is also equivocal. For the limit that defines the interior of sharing can turn into its opposite. It can turn into a boundary that excludes all the others from this common. The inclusive is revealed in the process to be its reverse, exclusive . In closing inwards, it expels outwards, and such is the common becoming intolerant of communitarianism .

IV- Is the universal an outdated notion?

The concept of the universal, which in its strong sense has been the driving force behind the development of European culture, is today in trouble. And this from two angles. Not only does it find itself to be in contradiction with itself, as we come to realize through encounters with other cultures that it is the product of a singular history of thought. But moreover, the singular history from which it springs in Europe does not in itself possess, when considered in its extension, the character of necessity that it’d imply in its principle. Indeed, once we leave behind a strictly philosophical perspective and consider the formation of this notion within the – more general – cultural development of what was to become Europe, we realize how much the advent of the universal is part of a composite, not to say chaotic, history: based on diverse, and sometimes even opposing planes, it is difficult to perceive what articulates these from within. I’ll mention at least three: the (Greek) philosophical level of the concept; the (Roman) legal level of citizenship; and the (Christian) religious level of salvation. What is the “necessary” relationship between them, and does it even form a “history”?

One thing, in any case, is certain, and that is that one form of the universal has been invalidated: that of totalization or completeness. When we believe we have achieved the universal, it’s because we do not know what’s missing from this universality. When the Van Eyck brothers, in the Ghent altarpiece, paint crowds from all over the world converging toward the altar of the mystical Lamb – while above is enthroned a God who appears to be both Father and Son, and in the background are walls that could equally be those of Jerusalem or Ghent – they are painting an outdated universal. Not only by virtue of the apocalyptic message that is expressed, but because this panoramic universal has no idea of what’s lacking in its totality. Because it takes itself for granted, and definitively arrived, and no longer cares about what it may lack: because it rests in its positivity and no longer gives rise to progress. It is no longer promising but it’s satisfied. Thus, for over a century, we have been able to speak of “universal” suffrage without considering that women were still excluded.

The universal, in other words, is to be conceived in opposition to universalism, the latter imposing its hegemony and believing itself to possess universality. The universal which we must campaign for is, on the contrary, a rebellious universal, which is never fulfilled; or let’s say a negative universal undoing the comfort of any interrupted positivity: not totalizing (saturating), but on the contrary, reopening the lack in any accomplished totality. A regulating universal (in the sense of the Kantian “idea”) which, because it’s never satisfied, never ceases to push back the horizon and keeps us endlessly searching. But this universal is precious not only theoretically, but also politically: it is what we need to claim for the deployment of the common. For it is this concern for the universal, promoting its ideality[idéel] as a never-achieved ideal, that calls on the common not to limit itself so soon. It’s this concern that must be invoked to ensure that the sharing of the common remains open, that it doesn’t turn into a frontier, that it doesn’t turn into its opposite: the exclusion from which communitarianism springs.

This means then, that the universal is not encountered immediately – or, at any rate, that it’s not guaranteed; that it is not given: it is not the soft pillow upon which our heads can rest. There’s nothing to say that the diversity of languages and cultures can fit into the “universal” categories that European knowledge has developed over the course of its history. On the other hand, if it is projected as a horizon before us, as a horizon that can never be reached, as an ideal that can never be satisfied, the universal is something to search for. The fact that it is posited as a requirement will encourage cultures not to withdraw into their “differences”, not to become complacent in what would be their “essence”, but to remain turned – stretched – towards other cultures, other languages and other ways of thinking; and to never cease, therefore, to rework themselves in line with this requirement, and thus also to mutate – in other words, to remain alive.

V- Gap / difference : identity or fecundity (resources)

The question then becomes: how do we deal with cultural diversity the moment we don’t let it disappear under the standardization of the uniform, and save the common from confusion with the similar? We usually talk in terms of “difference” and “identity”, an old pairing inherited from philosophy, which, since the Greeks, has proven to be so effective in the field of knowledge. But are they appropriate to this debate? Should we really account for the diversity of cultures in differential terms and according to specific traits, held to be characteristic, from which would derive an identity for each culture thus differentiated? I’m afraid we’re mistaken about the concepts here, and since these concepts are inadequate, the debate cannot move forward. That is to say, I believe that a debate on cultural “identity” is flawed in principle. That’s why I’m proposing a conceptual shift: instead of invoking difference, I propose to approach the diversity of cultures in terms of gap[écart]; instead of identity, in terms of resource or fecundity. This is not a matter of semantic refinement, but of introducing a divergence – or let’s say a gap – that will enable us to re-configure the debate: to get it out of its rut and re-engage it in a more assured way.

What difference should be established between “gap” and “difference”, if I want to define them in relation to each other? Both mark a separation; but difference from the angle of distinction, and gap from that of distance. Hence, difference is classifying, as analysis operates through resemblance and difference; at the same time, it’s identifying: it is by proceeding “from difference to difference”, as Aristotle puts it, that we arrive at the ultimate difference, delivering the essence of the thing, which its definition enunciates. In the face of this, the gap reveals itself as a figure, not of identification, but of exploration, bringing to light another possibility. As a result, the gap does not have a classification function, drawing up typologies, as difference does, but consists precisely in going beyond them: it produces, not a tidying-up[rangement], but a disturbance[dérangement]. We commonly say: “to make a deviation”[faire un eécart] (“how far does the deviation go?”[jusqu’ouù va l’eécart?]), that is, break away from the norm and the ordinary – such are already deviations in language or conduct. Deviation is therefore opposed to the expected, the predictable, the conventional. Whereas difference aims at description and therefore proceeds by determination, deviation engages in prospecting: it envisages – probes – how far other paths can be blazed. It is adventurous.

Let’s take a closer look at the difference at stake. Difference, insofar as it proceeds by distinction, separates a species from others and establishes by comparison what makes it specific. At the same time, it presupposes a neighboring genre within which the difference is marked, and results in the determination of an identity. But will this be relevant to approach the diversity of cultures? For, in so doing, once it has distinguished one term from the other, difference leaves that other aside. So, if I define (A) by difference from (B), once I’ve defined (A) in relation to (B), I drop (B), for which I have no further use: once the distinction has been made, each of the two terms forgets the other; each goes back to its own way.

In the gap, on the other hand, the two separated terms remain facing each other – and this is what makes the gap so precious to think about. The distance formed between them maintains the tension between what is separated. But what does it mean to stay “in tension”? In the gap, through the distance that appears but which is not unlimited and remains active, each of the two terms remains opposite the other. One remains open to the other, stretched by it, and never ceases to have to apprehend itself in this vis-aà-vis. This facing each other remains in action, alive; it remains intensive. If, in difference, in other words, each of the terms being compared – each having allowed their essence to be discerned by opposition – only has to fall back on this essence, apprehended in its purity, here in the gap, on the other hand, the two separated terms, staying in tension with each other – this “with” remaining active – never cease to have to measure themselves against the other: never cease to discover themselves in the other, both exploring and reflecting themselves through it. Each remains dependent on the other for self-knowledge and cannot withdraw into what would be its own identity. The gap, by the distance opened between them, has given rise to an “in-between”, and this in-between is active. In the difference, each having returned to its own side, having separated from the other to better identify its own identity, there is no “between” that opens up, and nothing more happens. In the gap, on the other hand, it is thanks to the between opened up by the distance that each one – instead of withdrawing into itself, resting within itself – remains turned towards the other, put in tension by it – in which the gap has an ethical and political vocation. In this between opened between the two, an intensity unfolds that overflows them and makes them work: we can already see what the relationship between cultures could gain from this.

It's true that we don’t know how to think about the “between”. For the between is not “being”. That’s why, in Europe, we’ve been unable to think about it for so long. Because the Greeks thought of Being in terms of “being”, that is, in terms of determination and property, and consequently abhorred the undetermined, they were unable to think of the “between”, which is neither the one nor the other, but where each is overwhelmed by the other, dispossessed of its own self and “property”. This is why, unable to think of the “between”, metaxu, they thought of the “beyond”, meta, of “meta-physics”. For the between, which is neither one nor the other, has no “in-itself”[en-soi], no essence, nothing of its own. Strictly speaking, the between “is” not. But this does not mean it is “neutral”, i. e. inoperative. For it is in the “in-between”, that in-between opened up by the gap and which cannot be absorbed, that “something” actually passes (happens) which breaks down belonging and property, which is built by difference, and identity is thus undone. We need to get out of thinking about (ontological) Being to begin to think this. This is what painters already did before the philosophers. Braque again: “what lies between the apple and the plate can also be painted.”

As for difference, its fate is linked to identity, and doubly so, on both sides. On the one hand, at its outset, beforehand, it presupposes a common genre, a shared identity, within which it marks a specification. And, on the other hand, when it reaches its aim and destination, it leads to ascertaining an identity, fixing the essence and its definition. In this way, as I’ve said, difference is identifying. But the gap takes us out of the identity perspective: it reveals not an identity, but what I’d call a “fecundity” or, put another way, a resource. By opening, the gap raises another possibility. It uncovers other resources we hadn’t considered, nor even suspected. By stepping outside the expected, the conventional (“make a deviation”), by detaching itself from the familiar, the gap, disturbing as it is, brings to the surface “something” that initially escapes thought. In this way, it is fruitful: it does not, by classification, give rise to knowledge; but, by the tension it creates, prompts reflection. In the in-between that it opens up – the intensive, inventive between – the gap gives us something to work on, because the two terms that stand out from it, and that it keeps in view, never cease to question each other in the gap that appears. Each remains concerned by the other and doesn’t close themselves off. And isn’t this what the relationship between cultures can take advantage of, rather than retreating into “differences”? To the point of recognizing what will be my thesis today: there is no such thing as “cultural identity”.

We need to consider the cost of muddling up concepts. We need to measure how dangerous – politically speaking – it can be to approach cultural diversity in terms of difference and identity : how costly it can be not only for thought, but also for history. A book like Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations is memorable in this respect. Of course, it was his description of the world’s major cultures (“Chinese”/ “Islamic”/ ”Western”) in terms of their differences and hence their identities, his establishment of characteristic features, and consequent tabulation and sorting into a typology that, convenient as it was, made the book such a success. Because of course, it didn’t disturb anything, it didn’t open up any departures from the conventional: it didn’t undo any of the clichés – prejudices – to which we like to reduce cultures in order to avoid bothering. By failing to recognize the heterogeneity inherent in every culture (its internal “heterotopia”, in other words), which is precisely what it unfolds from within, intensifying it through deviation, we also follow the easy path of classification and reassure ourselves. But is there a pure “core” of culture? Not only does Huntington fail to grasp anything interesting about these cultures, reducing them to banalities, but isolating them from one another, walling them off in what would be their respective specificities, their most marked differences, folding them in on their “identity”, he can consequently only end in a “clash” between them, as indeed he titled the book: a clash .

VI- “Dia-logue”

The famous “dialogue of cultures” has been imagined in many ways. We have notably dreamt of synthesis, with cultures coming together and complementing each other to form a unified whole. It’s a dream of a blissful understanding in which divergences fade away, where the common prevails over the diverse by absorbing it. The image has been complacently projected between “East” and “West” as the poles of human experience – East and West, the great symbolic marriage. These cultures would each rise on its own slope, and at the summit, be in harmony. But in what language will this coupling take place? Wouldn’t it be within Western categories, now globalized and reduced to Globish? The various cultures outside the West will be no more than exotic variations. The new globalized culture may well present itself as the Parliament of the world, which itself promises to be representative and democratically inclusive of all diverse currents, but this will not call into question the implicit cultural framework – illusorily universal, since it is only a camouflaged standardization – within which this gathering will take place. And like all motions for synthesis, this one, by resolving tensions and blurring differences, will be terribly boring, as I warned at the outset. Above all, the common will be factitious: it will not have made the diverse work to promote itself as common.

Or else, in order to highlight a commonality that would be authentic because it would be original, we’ll be asking what the common denominator between cultures would be. The opposite of synthesis is analysis: we break down all the diversity of cultures into their primary elements to discern what overlaps. If not as a core that would be identical, this commonality could at least be identified as a “comparable relationship” between terms, an “analogous” form of interaction or mediation. In its desire to contribute to a global, now planetary ethic, Unesco has worked hard in the last decades of the twentieth century to identify the points of agreement.

It has thus been said, as a minimal element, but one that would be irrefutable, that all moral conceptions and all religious traditions throughout the world advocate “peace”: “A vision of peoples living peacefully together”. After all, who wouldn’t wish for peace? – Well, Hegel? Or Heraclitus? Didn’t they explicitly call for war to highlight the function, including the ethical function, of the negative? Not only does any reduction of the diversity of cultures to some minimal element that would be common from the outset pull us back into the banality of truisms, but even these “truisms” are not true. A more significant logic has eluded them. If the complementarity of cultures always runs the risk of being merely the product of prior assimilation, but remains unsuspected, then the overlaps between cultures always run the risk, in turn, of being superficial, because they miss the most singular aspect of each culture. On both sides, by arbitrarily reducing the gap, cultures have lost their inventive resources.

A more serious – philosophical – attempt has also been made to discover a common logic of humanity in an ultimate foundation of reason that transcends all traditional paradigms of truth – those of adequacy with the thing or of an obviousness that imposes itself on consciousness. It is in the conditions of possibility of a meaningful discourse that, more radically, the community between men, as a “communicational” community, is to be sought (the path proposed by Apel and Habermas). The rules governing the use of language are rules whose validity has always been implicitly recognized as soon as one speaks, and which men would therefore a priori share. Since, as soon as we speak, to ourselves and to others, we pragmatically put them into practice, the consensus between men will no longer have to derive from any content of the statement, but from its form alone, and from what it necessarily presupposes by way of requisites, which, as such, are universal. And this undoubtedly applies if we remain within the framework of the European logos, as the Greeks conceived its requirements (already Aristotle’s principle of non-contradiction). But what if I leave Europe? Isn’t the whole discursive trickery of a Chinese thinker like Zhuangzi precisely able to thwart this supposedly common logic of communication? Then one would have to “speak without speaking”; or “find someone who forgets to speech to speak with him or her”… Or better still, isn’t the strategy of the Zen proposition (the kôan) to make this implicit protocol of rationality implode by sudden rupture? But will we then still be able to “dialogue”? And if the very protocol of dialogue is called into question, isn’t every principle of understanding between men, founding a cultural common ground, irretrievably abandoned?

The very word “dialogue”, if truth be told, is itself historically tainted with suspicion. In the first place, it’s because the West had lost its power that it began to “dialogue” with other cultures. Previously, on the strength of not only its “universal” values, but even more so of its logical formalization, it did not engage in dialogue. It imposed its universalism on other cultures, that is, colonized them by its triumphant rationality. And isn’t “dialogue” itself a soothing term that serves to conceal the power struggles that are constantly taking place between cultures, as well as within each language and each culture, with the coherences that prevail covering the others and burying them? Would Dialogue not claim to be a false irenicism? – Wouldn’t it adorn itself with a false egalitarianism? And firstly, in what language – the question comes up again – will this dialogue take place? If it’s in the same language (for example, globalized English or Globish), the dialogue is biased from the outset: as the meeting of cultures takes place on the terrain of one and the same language, that is, in its syntax and categories, other languages and cultures can only secondarily make their “differences” heard from this implied commonality, supposed to facilitate communication. This is often followed by a reactive demand for identity, all the more virulent as it is the only remaining response to this pre-imposed standardization.

But in the absence of dialogue, as we all know, it’s “shock” or clash – will we be able to get out of this alternative? Or, if dialogue seems like a last-ditch attempt to escape open violence, how can we give it a consistency that gives it dignity and establishes it as a vocation? If dialogue is a “soft” term, then we need to give it a strong sense, and once again, the best way to do this is to draw on the language itself and probe its resource. Dia, in Greek, means both gap and crossing. A dia-logue, as the Greeks already knew, is even more fecund the greater the distance involved: otherwise, we’re saying more or less the same thing, the dialogue turns into a monologue for two, and the mind will make no progress. But dia also refers to the path across a space, even one that may offer resistance. A dia-logue is not immediate but takes time: a dialogue is a journey. It is gradually, patiently, that the respective positions – apart and distant as they are – discover each other, reflect each other, and slowly elaborate the conditions of possibility for an effective encounter. It takes time. — In the face of which logos states the commonality of the intelligible, the latter paradoxically being both the condition and the goal of this dia-logue. That is to say that, through the very gaps, a commonality is generated such that – each language and each thought, each position allowing itself to be overflowed by the other – a mutual intelligence can emerge in this between that has become active – even if it is never completely realized (which is what the potential of the intelligible states). A commonality that is not the result of lessening the gaps or forced assimilation; but which, through this internal tension in the gaps that give rise to work, is produced: not imposed, or taken for granted from the outset, but promoted.

Because by gradually and reciprocally bringing each perspective out of its exclusion – not for all that from its position, but from the blocked, walled-in nature of its position ignoring the other – the dia-logue gradually brings out a shared field of intelligence where each can start to hear the other. But where does the intelligence effect come from, and what makes it binding (rather than just obliging wishful thinking)? It’s because each one, undoing, not its position, but the exclusivity of its position, starts to put the other’s position opposite its own – and this within its own position. For such is the power of the gap, now opposite, and its capacity for mutual rupture through the tension it creates. Hence, by integrating the other’s position in one’s own horizon, each puts one’s own position back to work, taking it out of its solitary self-evidence. For, by considering the other’s position no longer only from a defensive angle, but according to what is then discovered as another possibility, each perceives at the same time its own position, listening to the other, from that outside which is this other; and consequently discovers, with regard to the other’s position, the unilaterality of its own: the position of each is unsealed, its boundary overrun – a movement, by so discreet a shift, has thus begun. As soon as a dialogue is initiated – provided, of course, it is not feigned or false – and for as long as it lasts, an in-between arises – as each position opens up to the other (such is the entre[between] of the “entre-tien”[interview]) – where thought goes back to work. In this in-between, thought once again passes through and can be activated. Far from being self-indulgent or merely soothing, only the device of the dia-logue is in itself operative. Otherwise, there will only always be the forced assimilation of one by the other, i. e. its “alienation”, and we won’t be out of the power struggles.

But in what language, on a global scale, will this dialogue between cultures take place? If it can’t take place in the language of one or the other without the other already being alienated, the answer for once is simple: the dialogue can only take place in each other’s language – in other words, between these languages: in the in-between opened up by translation. Since there is no third or mediating language (especially not globalized English or Globish), translation is the logical language of this dialogue. Or, to borrow a famous phrase, but transferring it from Europe to the world, translation must be the language of the world. The world to come must be a world of between-languages: not of a dominant language, whatever it may be, but of translation activating the resources of languages in relation to each other. Discovering one another at the same time as getting back to work to enable us to move from one to the other. A single language would be so much more convenient, it’s true, but it imposes standardization from the outset. Interaction will be easier, but there will be nothing left to exchange, or at least nothing that is truly singular. As everything is immediately tidied up in a single language, with no more disturbing deviations, each language-thought – each culture – has, as I said, no choice but to stubbornly assert its “differences” as part of its identity. Translation, on the other hand, is the elementary and conclusive implementation of the dia-logue. It reveals the latter’s discomfort, its non-final character, always being repeated and never completed; but also its effectiveness: a communality of intelligence is elaborated in its in-between and comes to be deployed therein.

Intelligence, as developed by the diversity of languages and thoughts, is not a finite, arrested understanding (as was the Kantian understanding of categories). But the more it is called upon to traverse diverse intelligibilities, as in the dia-logue of cultures, the more it is called upon to promote itself: the more intelligent it becomes. In fact, it is one of the opportunities of our times, in the face of global standardization, to be able to open up to other coherences and, consequently, to other modes of intelligibility, through the discovery of other languages and cultures. Particularly for Europe: when encountering other languages and cultures, European thought does not have to invert its previous complacency, that of its universalism, into a guilty conscience, or even just relativism. Nor does it have to convert (to some factitious “Orient”), but it does have the chance to question itself from outside itself, and thus to put its reason back to work. For it is in the name of a logical universal, a universal in the a priori strong sense, and not by invoking some definition of man or human nature, always ideo-logical, that I posit such a commonality of the intelligible. This commonality of the intelligible is the commonality of the human: while men may never fully understand each other, nor between each other’s cultures, it is nevertheless to be posited in principle – as an a priori necessity (and transcendental of the human) – that they can understand each other and that it is only the possibility of understanding this diversity of the human – such as through languages – that makes the “human”.